by Dr. Stuart Donachie

Professor of Microbiology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

We might raise many cultures of microorganisms from a sample. The actual number of separate cultures depends on the number of different microorganisms in the sample, how many different growth (or culture) media we apply the sample to, and to other factors such as the temperature and duration of incubation. In this respect, differences in culture media cater to the needs of different microorganisms, as do different incubation temperatures and durations; some microorganisms take longer to grow, for example. We can also encourage other microorganisms to grow, or even not to grow, by incubating the samples on media in light, or by adding antibiotics to the growth medium to give less competitive microorganisms an advantage. As you can see, we could apply an infinite number of media and growth conditions in our quest to cultivate as many different microorganisms as possible.

Once we have a pure culture of bacteria on a medium, we determine if it belongs to a species that is already known, or is it one that is new and for which we might provide a formal binomial name. The methods we use to do this have changed a lot over the years; through much of the twentieth century they largely comprised a range of metabolic and biochemical tests, such as whether the culture could use a particular carbon source, or produce a particular enzyme. In the last 25 years or so, an alternative approach to provide insight into a culture’s identity has been developed. This was based on sequencing a specific gene in the culture’s DNA becoming easier, and the importance of DNA sequences in distinguishing and classifying all organisms increased greatly. Instead of running a battery of nutritional and enzyme tests, we now routinely sequence part of a gene in the bacterial DNA, the 16S rRNA gene. Knowing the sequence of nucleotides in part of this gene is enough for us to at least identify the genus the culture belongs to. The more nucleotides we have, though, the more confident we become that our culture belongs not only to a genus, but in some cases that it belongs to a certain species. If the nucleotide sequences of two 16S rRNA genes are identical over the length of about 1400 to 1500 nucleotides, meaning the nucleotides in each align perfectly, they are said to share 100% identity. If 99% of the nucleotides in two sequences of this length align, the sequences are not only said to be 99% identical, but we assume the bacteria from which these sequences were likely belong to the same species. This is a general rule of thumb to 98.6% sequence identity, although that value is only an indication of relatedness; we need more information to determine if the two bacteria in question belong to the same species or not. Historically, an in vitro laboratory method called DNA-DNA hybridization allowed DNA extracted from two bacteria to be compared; a value of less than 70% was considered definitive evidence that the bacteria belonged to different species. This could be supported by determining the combined percentage amount of the G and C nucleotides in the genomes. Within a species, the values cannot be more than one percent different, while that in different species in the same genus can vary markedly, such as by several to over 10 percent.

The in vitro methods of the past are no longer necessary. Although bacteria genomes vary considerably in size, with those of free-living bacteria ranging from less than one million nucleotides to over 10 million nucleotides, we now determine their G+C percent content and nucleotide sequence by in silico analyses of high-throughput sequencing data. Having sequenced and assembled a bacterial genome, we compare it nucleotide by nucleotide with others in an online database known as the Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS). Through a Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) we are provided a measure of the intergenomic distance, and where the outcome indicates, a statement that a potential new species [has been detected]. The GGDC also lists differences in G+C percentage contents between the genomes compared. Although we would now have strong indications through 16S rRNA gene and whole genome sequencing of a new species, we cannot propose that a new species exists without further work.

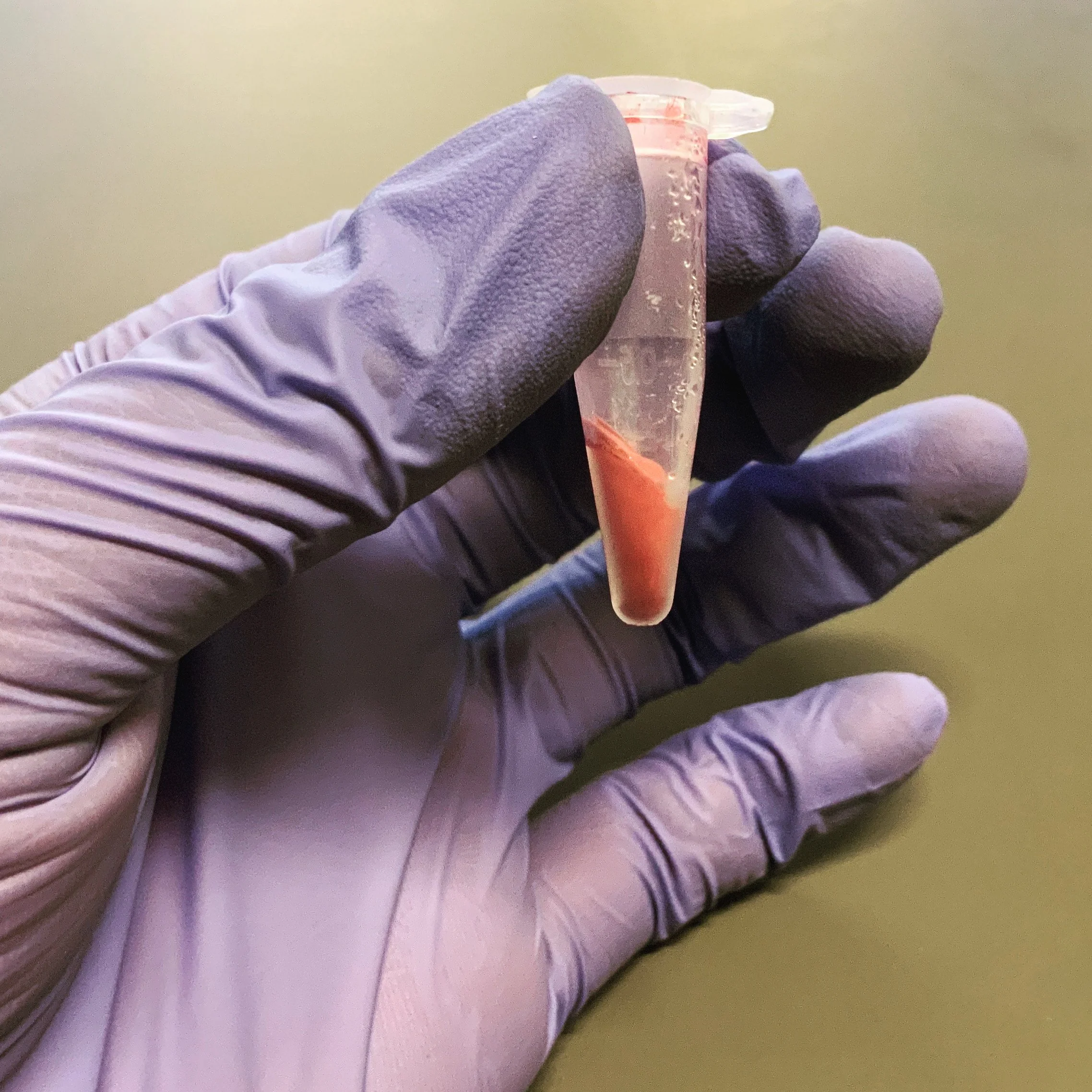

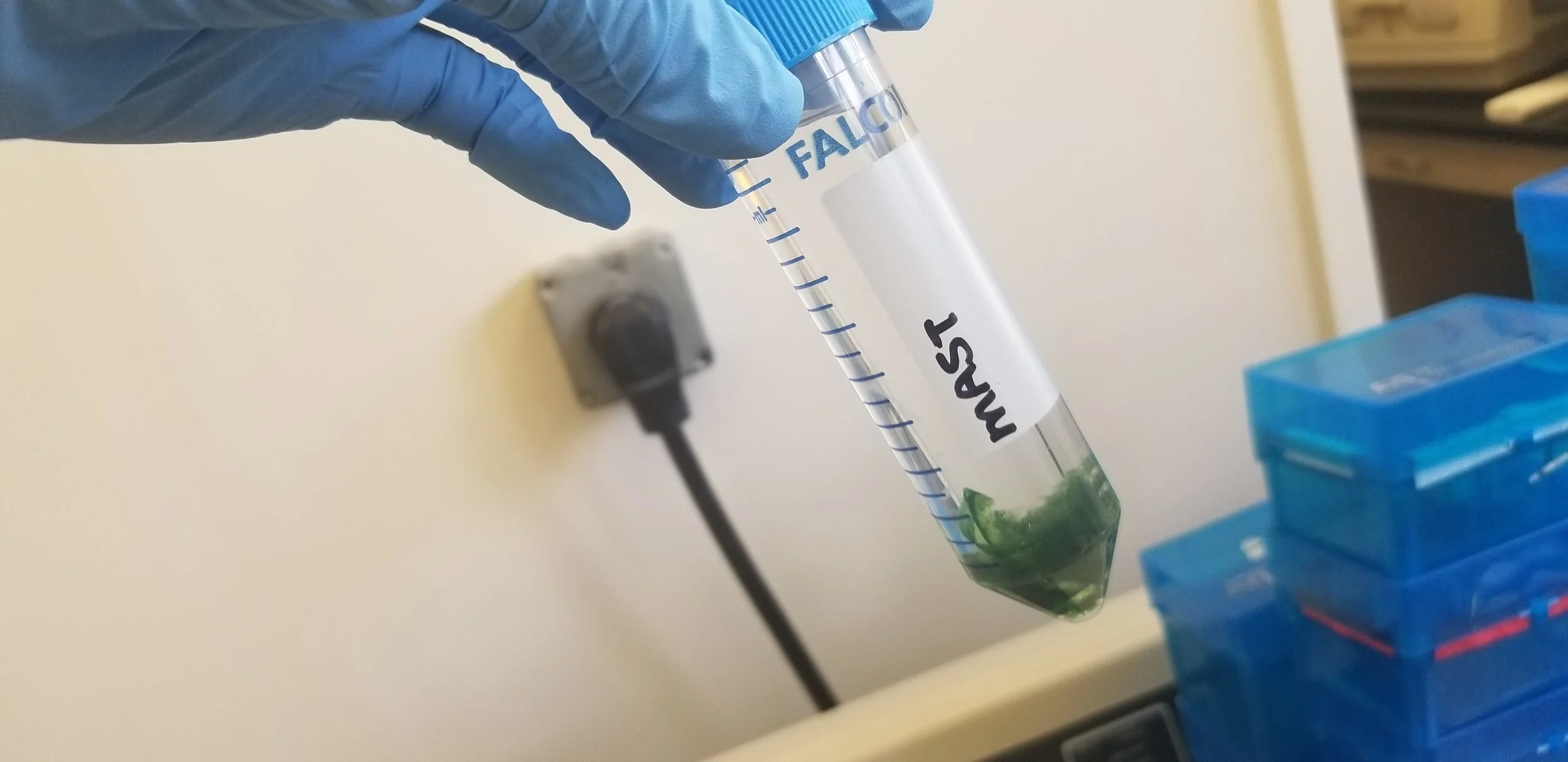

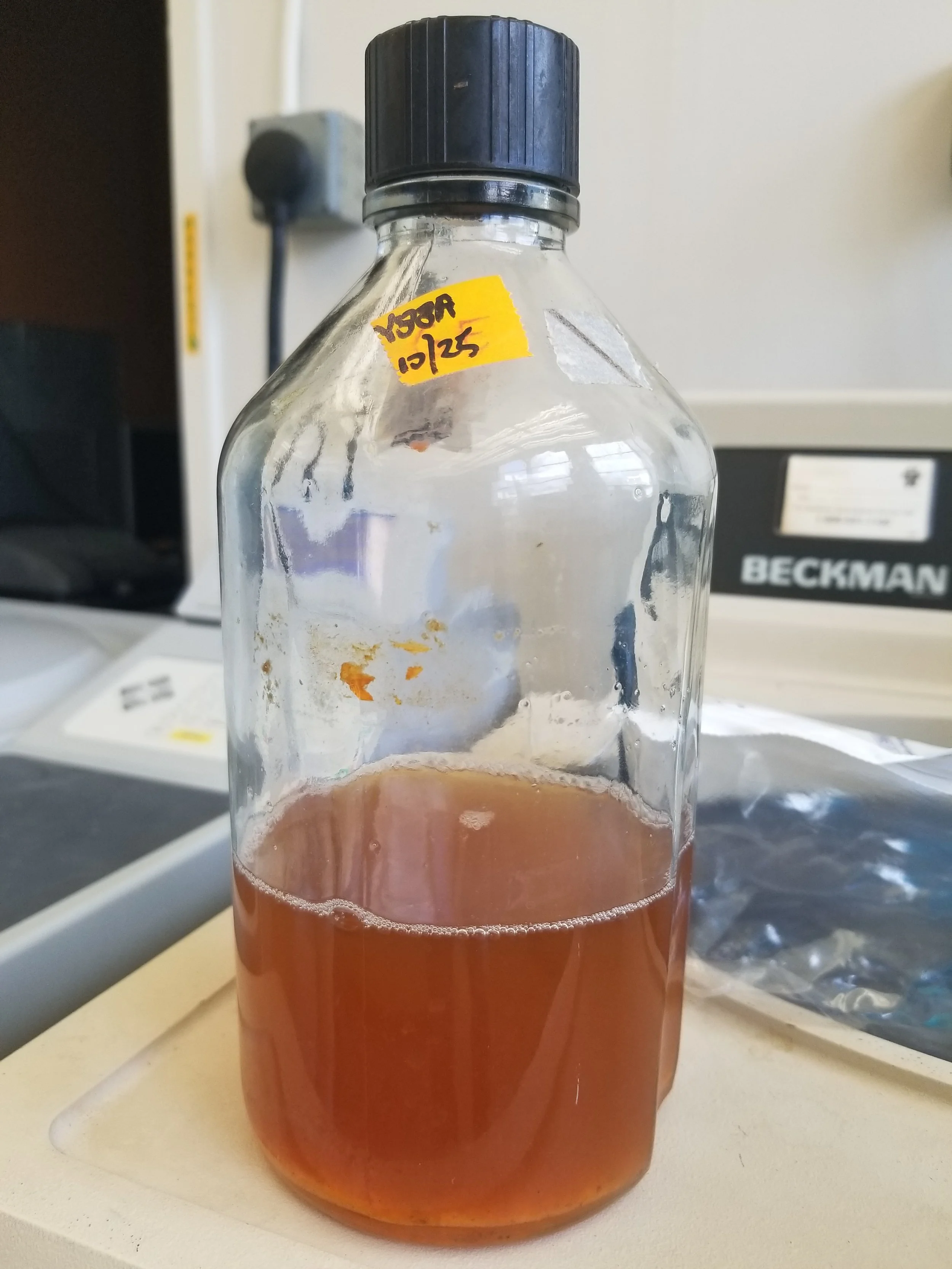

Examples of bacterial cultures growing in different lab media.

To publish a new species in a peer-reviewed scientific journal we familiarize ourselves with any requirements pertaining to what will be the host genus. These requirements are often referred to as the minimal standards, and include describing which characteristics distinguish the new species from its nearest relatives. These characteristics might include the presence or absence of a certain enzyme, or if the new species is motile while its nearest neighbor or neighbors are not. Here again, the G+C percentage of the genome is a crucial factor, as is the percentage nucleotide identity in the 16S rRNA genes. We also routinely determine temperature, pH, and salinity optima and ranges for growth. An absolute requirement is that a live copy of the new species is deposited in recognized culture collections in at least two countries; we prove that has been done by including with our manuscript certificates of deposit from those culture collections.

Once we’ve completed all laboratory tests and administrative procedures, which in the latter includes uploading gene and genome sequences to public databases, we must finalize the selection of a species name, and in some cases even a genus name. The new name must comprise two parts, as in the system known as binomial nomenclature. Well known examples are Homo sapiens, and Escherichia coli. Whatever name we propose must also conform to the rules of Latin grammar. If the new species will be placed inside an existing genus, then we only must develop the species name, or epithet. We do not name anything after ourselves! However, we have named species after places the new species was originally isolated from, e.g., loihiensis, kilaueensis, and papahanaumokuakeensis: these were assigned to the genera Idiomarina, Gloeobacter, and Terasakiispira, respectively. Coincidentally, the latter was a new genus we proposed to accommodate the sole new species, with the genus being named after a Japanese microbiologist, Yasuke Terasaki, to recognize his contributions to the study of spiral-shaped bacteria. Naming a new bacteria genus and species is quite an adventure. It is certainly one that might demand some patience.